Go Forth and Smolder

Civic Engagement

Social Justice

In order to analyze how the sense of responsibility for addressing the causes of human suffering developed in students by the ELSJ program is borne out in their everyday lives, we asked students “How frequently do you volunteer?”

These results further support the results of our previous question that indicated that those who had taken one ELSJ course generally saw service as less important than those who had not taken any ELSJ courses at all as they show that those who have not taken an ELSJ course are more likely to serve more frequently than once per quarter than those who have taken one ELSJ course. The only category in which those who have taken one ELSJ

Civic Life

The Civic Life goal states that the ELSJ program should help students to recognize the roles, rights, and responsibilities of citizens and institutions in society. We broke this down and realized that to a large extent, the issue of Civic Life can be seen as a sense of accountability and responsibility to your fellow humans. Part of our research question was asking whether the ELSJ program is creating a self-motivated desire to contribute to the common good, and part of a self-motivated desire to contribute is the belief that your contributions will actually matter. Accordingly, we asked students one question in order to analyze both the Civic Life goal of the ELSJ program and their belief of their ability to contribute to the world. We then followed this question with two additional questions, both focused on internal change and value shifts, based on the idea that in recognizing one’s role and responsibilities as citizen of the world, one must begin to transition their values and goals so that they extend beyond oneself. If the ELSJ program is truly instilling responsibility and accountability in its students, that change should be noticeable in their values and plans for future impact.

Overall Trends

After analyzing each of our individual questions, we decided that it was important to look at the trends and differences between those who had and had not taken ELSJ classes. In order to accomplish this goal, we quantized the answers of each multiple choice question from zero to five, with zero being the lowest and five being the highest, sorted the answers based on the number of ELSJ courses each respondent had taken, and then took the average of all responses of each group. This allowed us to compare the average responses of each group to the six answer multiple choice question and the five answer multiple choice questions on the same chart, seen to the top right.

Additionally, we combined the results from each of the three open response questions, comparing the percentages of “positive” responses found from each question, with the “above average”, “showing external values”, and “showing external values” categories considered to be positive, as seen in the chart to the bottom right. These two charts allowed us to analyze the overall trends in the data.

We found that, in general, those who have taken one ELSJ course actually value the things the ELSJ program is supposed to instill in its students less than those who have not taken an

In order to measure Civic Engagement, we focused on the portion of the goal that said that students ought to participate actively as informed citizens of society and the world. To assess this we asked the question: “Do you vote regularly?”

Because voting is how we express ourselves to the government, and the organizations with the power to make real social changes, a person’s history of voting or not voting indicates their basic level of engagement with the society around them. By voting, students can help to shape the policy of our governing body and help our government decide to address the social issues that are important to us.

Within our survey, we broke down all of the responses by the number of ELSJ classes taken, and then assessed relative voting percentages as seen in the chart to the right, omitting the multiple ELSJ class category due to its small sample size. Our results were interesting. There was a definite trend that people with fewer ELSJ classes were more likely to vote than those who had taken more. This trend is worrying, but not terribly so, due to the small sample size. However, if these results hold up within a larger sample, this would be an indication that the ELSJ program is not meeting its goals. There are some mitigating factors we must consider. For instance, some of the trends in the data can be explained due to the practical difficulties of voting as a student: a student from out of state must register to vote in their home state, as a long distance voter and send in their ballot about two months ahead of the actual vote in their state. Additionally, as many Santa Clara students are not American Citizens, they may not be able to vote while in America. However, each of these factors can apply to anyone, regardless of the number of ELSJ classes they have taken, so these factors will have minimal effects on the collected data. If the students who take more ELSJ courses become less likely to vote, it means that they are not leveraging the greatest resource they have to help the communities which they have served in, and are thus failing to be the active, informed citizen that the program strives to create. This helps us to answer our research question by indicating that, currently, the ELSJ program is not fulfilling the core learning goal of civic engagement and is thus not fulfilling one of the core educational goals of Santa Clara University.

Service Frequency

In order to address whether students are gaining a sense of responsibility towards addressing the problems of our world through the ELSJ program, we asked students the question “How important is service to you?” This was formulated as a multiple choice question with five possible answers, each later assigned a numerical value. Our results are shown within the chart to the right, separated by the number of ELSJ classes each respondent had taken at the time of the survey.

Notably, the responses to this question indicate that people who have taken one ELSJ class generally feel that service is less important than those who have not taken an ELSJ class at all, while those who have taken two or more ELSJ classes feel that service is far more important than

Service as a Responsibility

In order to assess the Social Justice learning goal, we decided to break it down into two parts. First, we wanted to see whether students saw service as important and a responsibility, and second, we wanted to see if that belief was backed up in their daily lives. The learning goal itself states that students should develop “a disciplined sensibility toward the causes of human suffering and misery, and a sense of responsibility for addressing them” (Learning Goals and Objectives). Our survey questions break down the second half of the goal, in particular the sense of responsibility for addressing the causes of human suffering and misery. The question of the importance of service is designed to indicate whether the respondent feels the sense of responsibility towards addressing the causes of human suffering, the stated goal of the program. The second question looks into the real world effect of that, seeing whether that sense of responsibility that should be cultivated by the program about service participation translates into actual service to the community. The third question is meant to investigate the relative difference between the hours of service per month that they think their peers contribute and the average hours of service per month amongst their peers as calculated based on the question of service frequency, essentially an analysis of how dedicated to service students think their peers are. These questions will help us to answer our research question because they indicate whether students are gaining the self-motivated desire to contribute to the common good as well as directly assessing the success of the ELSJ program’s stated goal of Social Justice.

those who have taken one or fewer ELSJ classes. This leads to two interesting conclusions. First, the ELSJ program is not succeeding in instilling a sense of responsibility to serve the community and to combat the sources of human suffering within its students in just one class. This is indicated by the fact that people who have taken one ELSJ class believe service is less important than those who have not taken an ELSJ class at all. If the program were succeeding in meeting its stated goal of developing a sense of responsibility for addressing the causes of human suffering, than those who have taken one ELSJ class should generally feel that service is more important than those who have not.

class outstrip those who have not taken any is in the once per week category. However, even this is offset by the fact that those who have not taken an ELSJ class are more likely than those who have taken one ELSJ class to serve more than once per week. In fact, no respondents who had taken one ELSJ class served more than once per week while four of those who had not taken an ELSJ class did: a stark difference. The fact that 64 percent of people who have not taken an ELSJ course volunteer once per month or more frequently while only 50 percent of those who have taken one ELSJ course do the same speaks volumes about how engaged in service each group is. This can be partially accounted for by considering that those who have taken one ELSJ classes are most likely older students, as first years rarely take ELSJ classes. Older students typically have more intense schedules and more academic responsibilities, in addition to jobs and other extracurricular responsibilities, restricting time for volunteer work. However, the results from this question are consistent with those from the question about the importance of service, indicating that the differences between those who have taken one ELSJ class and no ELSJ classes cannot be dismissed based solely on the more intense schedules of older students.

Connections to Current Research

Our research focuses on a relatively unexplored topic, as it is an examination and evaluation of the learning outcomes of SCU’s ELSJ program in particular. However, there are a variety of sources that help to shed light as to why our findings are what they are.

First, Seider, Rabinowicz, and Gillmor argue that the discouragement that students feel when they discover they cannot impact a community as much as they hoped significantly reduces both their enthusiasm for future service and their self-efficacy, or belief that they can make a positive difference in the world. This supports the interpretation that the decline in voting, service frequency, and belief in service as a responsibility seen in our data is due to the same discovery of the difficulties of service. Additionally, they provide a potential solution for this shared problem: requiring that, prior to the actual service, students reflect on their expectations of the experience and discuss those expectations within a class setting (Seider, Rabinowicz, and Gillmor). This solution is completely feasible and easy to implement for the ELSJ program and could help to solve one of its current issues.

Second, Barnes writes to disprove the myth that all service-learning has inherently positive and meaningful results. Her research shows that while service learning increases student awareness about service agencies in the community, it changes little to nothing in student character or motivation, particularly when left unmeasured and unchanged (Barnes). This mirrors our findings, indicating that our curriculum may be assuming that service learning, on its own, does more than it truly does. There is no readily apparent solution to this potential problem, but a renewed focus on measurement and assessment of the teaching methods of the ELSJ program could help us to overcome this issue. Chan Cheung-Ming, Lee, and Ma Hok Ka also support this particular solution, arguing that specific, measurable learning goals and frequent evaluation are necessary to have a successful service learning program as they allow the administration to truly see what is working and what is not, helping to spur timely adjustment to any problems.

Perceived Service

In order to evaluate how dedicated to service students believe their peers are, we asked the question, “How much time does the average Santa Clara student devote to community service per month?”

We asked this in a short answer format, allowing students to come up with their own numbers as they felt was appropriate. In order to evaluate this data, we broke down the responses from the question of service frequency, and assumed that that data was representative of the whole SCU population. We then calculated, based on the percentages of responses corresponding to each of the six frequency values given, the expected instances of service per month for an SCU student. Finally, we assumed

that each instance of service was, on average, 2 hours long. This gave us an expected average value of 4.54 hours of service per month. We then evaluated each response as greater than or less than the average and compiled the data in the chart above.

Our results show a clear difference between those who have taken an ELSJ class and those who have not, with those who have not taken an ELSJ class being about 10 percent more likely than those who have taken an ELSJ class to believe that their fellow students are performing more service than average. Although not pictured, we also found that two of the three respondents who had taken multiple ELSJ classes believed their fellow students served more than the calculated average. These findings are interesting. Although this question does not indicate anything about the respondent’s dedication to the goal of Social Justice, it does show that those who have taken one ELSJ class believe that their peers are less Social Justice oriented than those who have not. This is not necessarily a bad thing for the ELSJ program, as it could point to the disillusionment of those who have taken one ELSJ class. In serving for their class and being made aware of the difficulties present in the world, students who initially thought that their peers were serving more in the community around them could see the pure volume of work that needs to be done and begin to believe that their peers were not doing as much as they initially believed.

Accountability

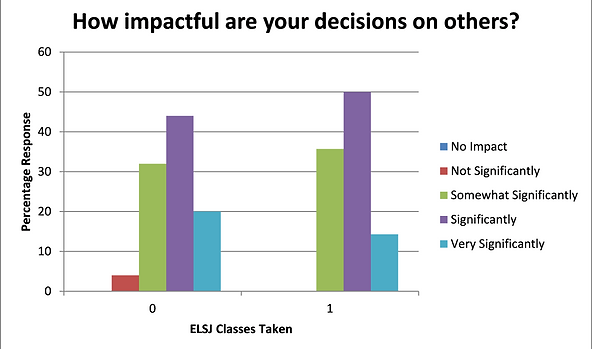

In order to measure students’ perceived responsibility and accountability to those around them, we asked the multiple choice question “How impactful are your decisions on others?”

Our results indicate that the ELSJ program is fulfilling its “Civic Life” goal to develop in its students a sense of accountability for their actions. Those who had taken one ELSJ course responded very similarly to those who had not taken an ELSJ course, and although more people who had not taken any ELSJ classes believed that their actions "very significantly" impact the world around them, those who had taken one ELSJ course believed, on average, that their actions were slightly more impactful than those who had not. While this is not a

huge success, it shows that the ELSJ program is showing students that their actions can impact others, hopefully giving them a sense of accountability to the people around them and a sense of responsibility to act for the benefit of their society. Again, the ELSJ program seemed to serve those who had taken two or more ELSJ courses very well, although our results may be inaccurate due to the small sample size. This is the most hopeful result we have received yet for the current ELSJ program as it shows that students who take one course are being positively impacted by the program, albeit to a very small extent.

Core Values

In order to measure the change in core values that the ELSJ program ought to create in its students, we asked the open response question “What are your three core values?”

We received a variety of responses, ranging from “Service” to “Fun” and covering everything in between. To code this rather diverse data, we looked for one significant quality: if one or more of the respondent’s three core values was externally focused, we counted that person’s response as “Showing External Values”, and if none of the respondent’s three core values were externally focused,

we counted that person’s response as “No External Values”. In this context, external values are values that are aware and focused on those outside of the respondent. For example, responses like “compassion”, “service”, “generosity”, and “justice” were considered external values, while responses like “skepticism”, “happiness”, “integrity”, and “optimism” were considered to be internal values. This is not a judgement of the worth of these values, but rather an examination of whether the ELSJ program is successful in instilling external values and thinking within its students.

The results we gathered were very interesting. As shown in the chart above, those who had not taken an ELSJ class actually showed a much higher likelihood of holding external values than those who had taken an ELSJ class. Additionally, all three of the respondents who had taken two or more ELSJ classes responded with at least one external value. Given the rest of our data to this point, this result was not particularly surprising as it continues to point to the same worrying trend: people take an ELSJ class and take away the opposite of what the program desires to instill in them. This creates a difficulty for the idea that the exposure to the difficulties of service in the real world is responsible for the decrease seen earlier in the evaluations of the Civic Engagement and Social Justice goals because, even if students were disillusioned, discouraged, and in the process of confronting the difficulties of social justice, their values should have been impacted. Seeing the world in all of its cruelty and learning about your responsibility to help heal the world should not result in the internal retreat we see evidenced in this data. However, it is possible that students, as they get older and closer to entering the real world, are forced to think of themselves first more often and are thus less likely to consider external values to be “core values”. While this is a possibility, it still does not change the fact that this shift inward is the exact opposite of the effect that the ELSJ program strives to achieve.

Career Impact

To measure the realization of the Civic Life goal through students’ vocational goals, we asked the long answer question “What impact do you hope to have through your career, whatever it might be? Why?”

We received responses from “Help develop tech/software to make people's lives easier…” to “Impact on what? I hope that it makes me happy and that it will be worth this extremely expensive tuition,” clearly demonstrating a wide range of responses. Similarly to the previous question, we coded this data by determining whether or not each answer showed evidence of external values. Within this context, we defined “Showing External Values” as any response where the respondent included something about

bettering the world around them, with qualifying responses ranging from “A better world/future for everyone :)” to “As an engineer, I hope to create products or services that directly increase life and the standard living in my community.” Conversely, an example of those that showed no evidence of external values is “I don't know that I'm hopeful enough to think I'll be able to have an impact through my career…”.

This question resulted in a mixture of positive and negative findings. As seen in the chart above, the overwhelming majority of all respondents responded with externally focused impacts, but we still see the same decline in the percentage of externally focused responses from those who have not taken ELSJ classes to those who have taken one ELSJ class. Not shown in the chart are the responses of those who have taken multiple ELSJ classes, but all three of those respondents showed significant external focus. The overwhelmingly external response is impressively positive, but it is also a significant outlier from the rest of our data. The uniformity of the increase in external response across all levels of ELSJ experience could point to the possibility that the phrasing of the question, particularly the use of the word “impact”, skewed the results to the point that students answered with primarily external impacts despite the fact that they may not be part of their goals and motivations for their vocational choice. Additionally, this could be due to the demographic of students at SCU. As a school focused on Social Justice, it would logically draw a high proportion of externally minded students. In either case, the positive nature of the data does not stop the same trend from exhibiting itself: those who have taken one ELSJ class were about 10 percent less likely than those who have not taken an ELSJ class to exhibit external values in their vocational goals.

ELSJ class, across the board. While the results are nearly identical between the two groups on the question of accountability to the community, in all other categories those who have taken no ELSJ classes actually embody the virtues that the ELSJ program wants to instill in its students better than those who have taken one course. Although our results are not statistically significant, these results are still alarming as they indicate that the ELSJ program is actually reducing students commitment to the goals of social justice, civic engagement, and civic life across the board when those students only take one ELSJ course. While our sample size of students who have taken multiple ELSJ classes is very small and their results are not shown on our charts, these students who have clearly bought into the program, who have gone back beyond the core requirement, clearly value and live out the social justice and civic life goals more than either of the other two groups. Their voting rate, and thus civic engagement is low, but that could simply be an effect of the extremely small sample size. In general, when students only take one ELSJ course they are less likely than students who have not taken an ELSJ course to possess the virtues the ELSJ program is attempting to instill in its students.

These overall results could, however, be seen as a success. If we focus solely on the stated learning goal of Perspective, or awareness of social justice issues and understanding of other cultures, and the student experience, taking an ELSJ course should, in fact, expose students to the difficulties present in social justice and service, complicating what were previously perceived as simple issues. Notably, those who have not taken ELSJ classes are typically younger than those who have taken ELSJ classes. Although we did not compile data to support this claim, logically those who have taken more classes are more likely to have taken more ELSJ classes. This difference in age across categories could account for some of the differences seen in our findings, as the natural maturation process associated with aging and the college years likely impacts students' perception of social justice. This stripping away of a naive and idealized view of social justice could, in fact, give the results seen within our study. Assuming that those who have not taken any ELSJ classes have an idealized view of social justice, we would expect them to be more idealistic, and thus more adherent to the current learning goals of the program, than those who had taken one ELSJ course and were currently wrestling with the newfound challenges encountered during the class.

Under this paradigm, we would also expect those who had taken two or more ELSJ classes to have come to accept the challenges inherent in social justice and to have realized its true worth, resulting in greater adherence to the learning goals of the program than either of the other two groups. Although this interpretation explains the data to a certain extent, it indicates that the current ELSJ curriculum must change to reflect this understanding, requiring the second class in order to allow students to confront the challenges of social justice, and come out with a more complete understanding. However, this is not a perfect explanation as it fails to explain the reduction of external values seen in the Civic Life section. This internal struggle to accept the difficulty of social justice should not result in the reduction of external values. These findings necessitate further investigation as they call into question the current learning goals, structure, and curriculum of the current ELSJ program.

1. In the evaluation of this and the rest of our open response questions, we dealt with non-responses, or people skipping the question. We left these non-responses out entirely when coding the data, not considering them to be positive or negative responses in order to avoid negatively coloring the results.